Argentina’s new president, the self-styled anarcho-capitalist Javier Milei, takes on one of the world’s toughest economic challenges on Sunday.

The country is a big food exporter and used to be one of the wealthiest nations in the developing world, but decades of mismanagement have wrecked the economy and created a web of artificial price and exchange rate controls that have produced huge distortions.

A libertarian economist whose beloved pet dogs are named after ideological heroes such as Milton Friedman, Milei campaigned on promises of taking a chainsaw to the state, closing down the central bank and replacing the peso with the US dollar. But he has made a dramatic shift towards moderation since winning the election.

As Milei’s first day in office approaches, what are the main economic challenges that he will inherit?

Chronic overspending

At the root of Argentina’s problems is the government’s chronic overspending. The size of the state has almost doubled over the past two decades, with the government expanding the public sector payroll, handing out hefty fuel and electricity subsidies and boosting welfare programmes.

Public sector employment rose 34 per cent between 2011 and 2022, while private sector jobs increased only 3 per cent in the same period, according to a report by the IERAL think-tank. This has led to continual budget deficits of more than 4 per cent of gross domestic product, despite tax levels that are well above the Latin American average.

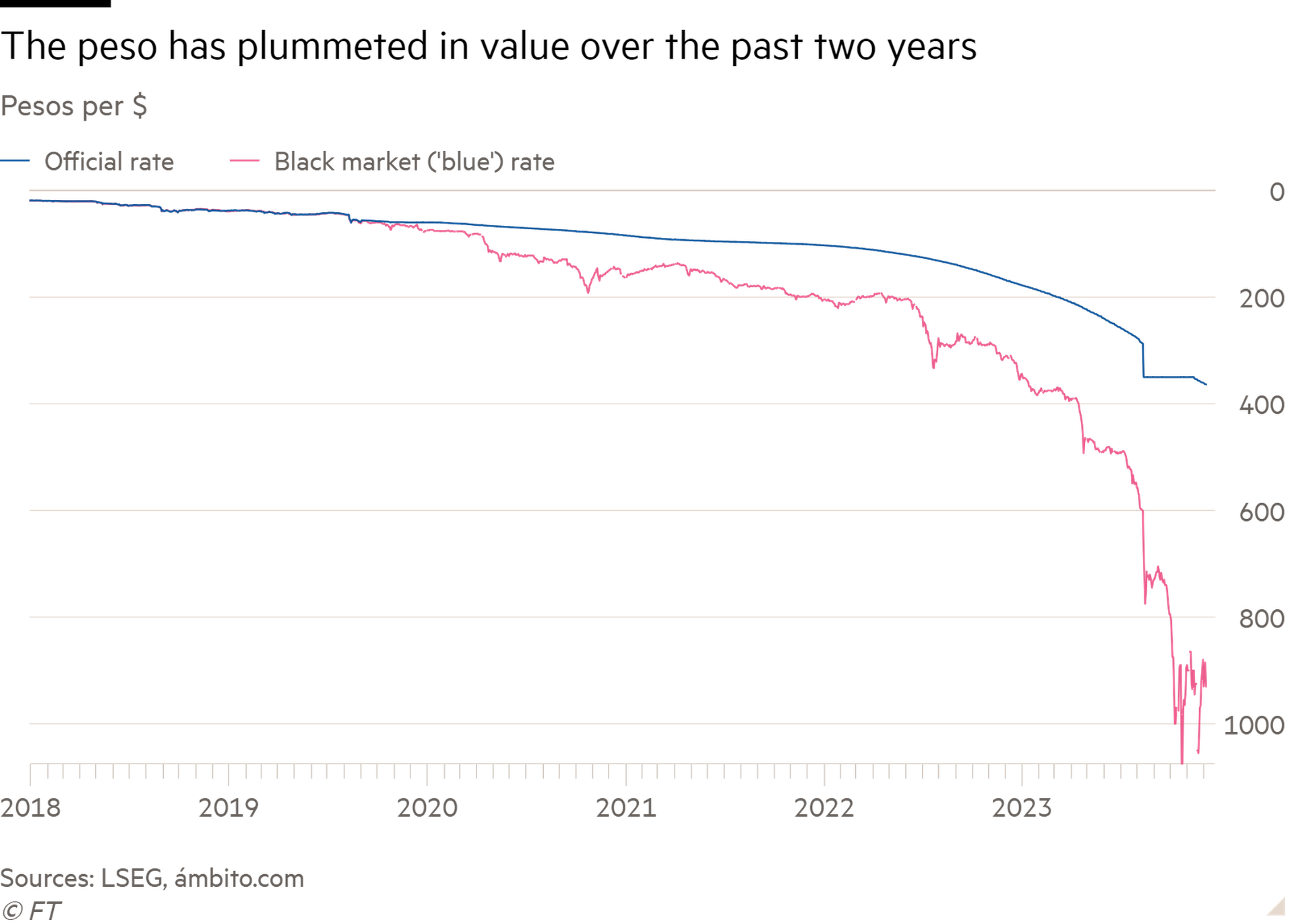

Decline in the peso

With the country cut off from borrowing on international capital markets since its ninth sovereign default in 2020, the current Peronist government has resorted to printing money to help fund the deficit. The money supply has exploded and the value of the peso has collapsed. Tight controls on foreign exchange have prompted a flourishing black market in the dollar and encouraged exporters to hoard goods, rather than ship them at artificially low official exchange rates. Argentina’s net international reserves are now negative, according to most economists.

Stubborn inflation

The collapse in the peso’s value has fuelled inflation, which is now among the highest in the world. JPMorgan expects Argentina’s annual inflation to reach 210 per cent by the end of this year and warns that it is likely to rise further in the first half of next year — which could put it on a par with levels in Sudan and Zimbabwe. The central bank’s reference interest rate has shot up to 133 per cent to compensate depositors for rampant inflation.

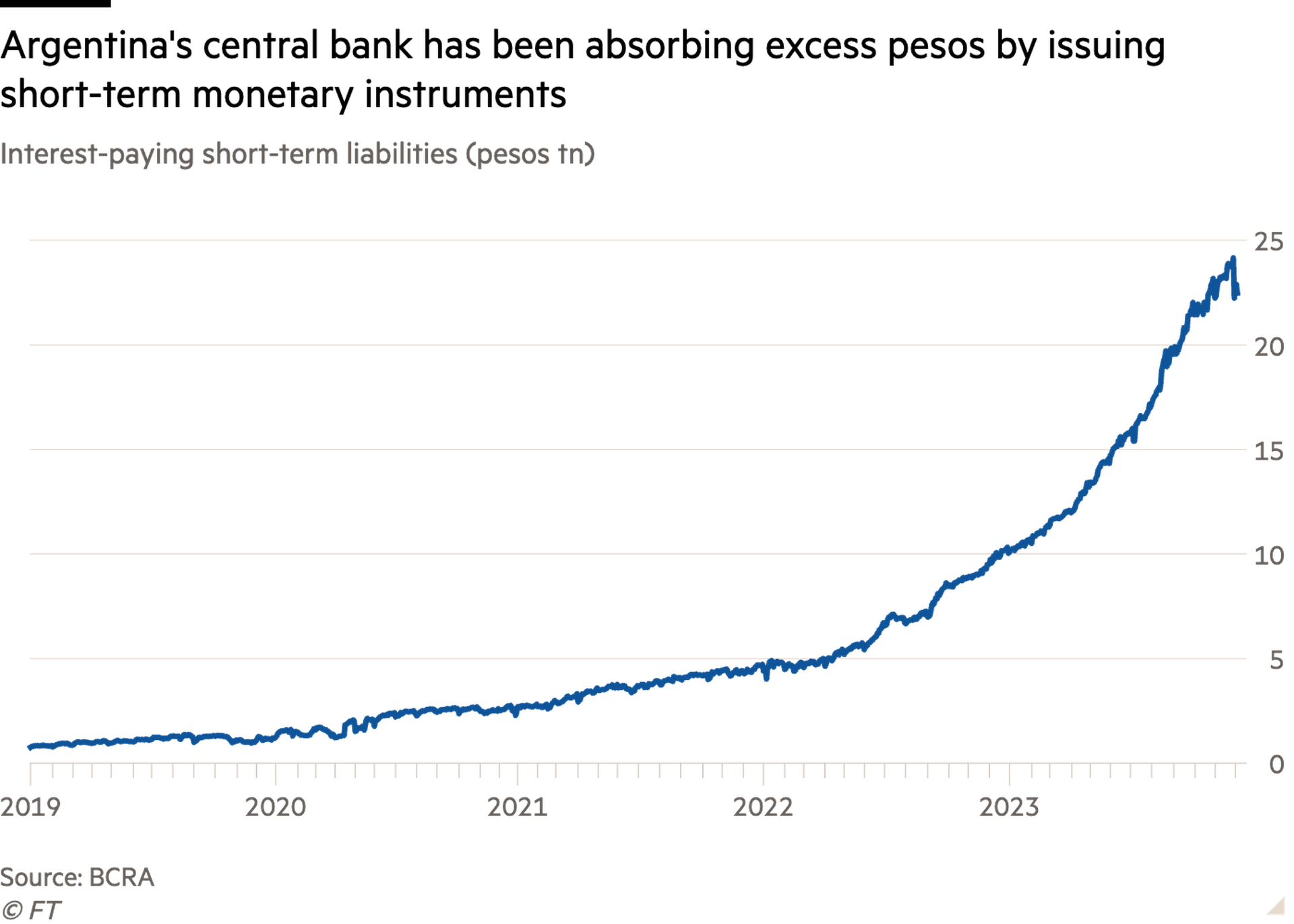

Rising liabilities

To soak up a large overhang of pesos in domestic markets, Argentina’s central bank has been issuing short-term interest-paying notes on local money markets. Those liabilities are more than 20tn pesos — nearly three times the monetary base — and generate hefty interest payments to the banks that hold them.

After a markets crisis in 2018, Argentina’s previous centre-right government turned to the IMF for a record-breaking bailout. It still owes the fund $43bn from that rescue, making it the biggest debtor to the Washington-based organisation. Argentina in 2020 also restructured $65bn of debt owed to private sector creditors. The IMF estimates that Argentina’s total foreign currency sovereign debt is $263bn.

Cultural money habits

Argentines hold large amounts of dollars in cash within the country, as the US currency is widely used for savings and big transactions, such as property purchases. Central bank chief Miguel Pesce estimated in 2021 that Argentines held $200bn in cash within the country, which he said was 10 per cent of all US dollars in circulation in the world. A draft bill in Argentina’s Senate last year estimated that its citizens held another $418bn in mostly undeclared assets abroad.

The daunting task of straightening out Argentina’s dire public finances that Milei and his economy minister-designate Luis “Toto” Caputo face will include unwinding the current controls and distortions as well as stabilising the economy, all without triggering an explosion in inflation or a collapse in market confidence.

Alberto Ramos, chief Latin America economist at Goldman Sachs, said if Milei succeeded in curing Argentina’s economic ills, “it will be the best emerging market story in decades”.

“He may try to do the right thing but may not be able to,” Ramos added, citing the difficulties of governing. Then there is the inherent volatility of the economic situation. “You are dealing with nitroglycerine. It can ignite overnight. Once you start the economic adjustment, you can lose control.”

Were that to happen, Ramos compared the challenge to a Formula One racing car that goes into a high-speed skid. “In this situation, there are no good or bad drivers because there is nothing you can do,” he said. “You take your hands off the wheel — and luck, the conditions and the state of the track will dictate where you end up and how much damage there is.”

Additional reporting by Ciara Nugent